|

From green to red, hot to cold, sun to snow, October has shown the breadth of what one transitional month is capable of. This October I didn't make it out nearly as much as I would have liked, but every time I was able to, I was not disappointed. As we sit here on this cold, dark, last day in October, it's hard to think back to the 80 degree days we had just a few weeks ago. Yesterday I was out walking at the Bog when all of a sudden I had the impression of springtime, the crisp air, the occasional sun, but what sold it for me was the spring birds singing in the trees! Fall migration sends our feathered friends back to their winter homes, not usually in as dense of groups as the spring travel, but on this occasion the trees and shrubs were full of song. Don't forget to put your feeders out to help these birds on their journey! Barne's PreserveOct 3rd Oct 27th Brown's Lake BogOct 3rd Oct 10th Oct 30th Killbuck Marsh Wildlife AreaOct 22nd Wilderness RdOct 3rd Wooster Memorial Park (Spangler)Oct 10th Oct 22nd

0 Comments

A perennial plant in the aster/daisy family, the common sneezeweed can be found in most of the US enjoying rich moist soils. It blooms late summer through fall providing food for bees and butterflies. As a composite flower it has both large showy ray flowers that look like petals which surround the smaller disk flowers that make up the center. The bright yellow 'petals' are wedge shaped with three lobes on the outer edge that droop away from the central disk - this is the easiest way to tell them apart from similar flowers like the oxeye sunflower. The genus name, Helenium, is a reference to Helen of Troy. The legend says that these flowers sprang from the ground where Helen's tears fell. Although the name might make you think this plant is a cause of seasonal allergies, it (much like the goldenrod) has too heavy pollen to be blown through the air and instead has to be pollinated by insects (again, ragweed is the main discussed culprit of fall allergies). However, at one time it was used to make a form of snuff to induce sneezing - the sneezes were a desirable way to rid the body of evil spirits. No part of this plant is edible to humans.  Swamp Smartweed Swamp Smartweed The Polygonaceae family is a family of flowering plants sometimes known as knotweed or smartweed - buckwheat. In total there are about 1200 different species broken down into 48 different genera. These plants can be found world wide, however, the majority grow in the North Temperate Zone. Generally growing as small herbaceous plants with swollen nodes, there are a few trees, shrubs, and vines in the family as well. Some of the most well known members of this family are: Wild Buckwheat, Lady's Thumb, Pennsylvania Smartweed, Swamp Smartweed, Curly Dock, Japanese Knotweed, and Virginia Knotweed. This family of plants is more than just delicate dainty flowers growing in damp soils (as I once thought), they can have large seedpods (as with the curly dock), they can be invasive, they can be used for food, and they can be spotted all around Ohio.  Common Beggar-Ticks are, just that, common. This Native wildflower likes disturbed soils, barnyards, waste area, swamps, meadows, fields, etc. Its name is derived from the seeds that cling to people as they pass by, if you've spent any time out in the woods I'm sure you've encountered them, long oval pod with two little 'grabbers' on the end. While they seem like a nuisance, these plants are important food sources for a wide variety of bees and flies (nectar), birds including ring-necked pheasants enjoy the seeds, and rabbits & beetles like the leaves. If you follow the blog for any length of time, you probably know spring wildflowers are my favorites - not only are they beautiful but they are the sign that warm days are to come! After April and May we tend to divert our attention to the new things that are emerging, new plants, new birds, etc.

So what happens to the spring wildflowers after spring? That is an interesting question that is going to take us to a few different places, hold on, let's go! In the spring, it's dark (but getting lighter), it's cold (but getting warmer), and some mornings it's hard to leave the bed (or in the case of flowers, the ground). How, after a long winter do these beautiful, showy, flowering plants have the strength to push up through the nearly frozen ground to bloom? The bloodroot for instance, in the spring you'll see the flower rise up and bloom before the leaf unfurls from the stem. If we think back to elementary school science we know that plants need sunlight to grow and gain strength, that basically the leaves are like solar panels channeling energy through the plant, so how does the bloodroot bloom and grow with no leaf present? The secret to these early spring bloomers can be found in fall. Through the summer you'll find that many plants shoot right up, grow, then die and are gone for another season - cleavers or bedstraw is a good example of that. Just after the spring bloom the cleavers with their 'sticky' vines rise up and cover everything, in about a month's time they grow, cover, bloom, seed, and by the end of the next month you can hardly find a trace of them. If you look under all the summer growers, you'll find the wide leaves of the spring bloomers still holding strong. Even after a full summer season has come and gone you'll be able to find the leaves of these modest plants. Granted, you won't be able to find all the spring bloomers in the fall. Why, after all the other plants have tried to crowd them out, do we still find these plants growing long after their bloom & seed? To gather and store energy. Thats right, these plants grow and gather as much sunlight and energy through the span of the year so that when spring comes around again, and all the leaves are gone from the trees, they can send out all that energy to grow and bloom as fast as they can so they can soak up the sunlight before the trees fill out and their sunlight will be highly limited. Now not all spring flowers go this route, for example the squirrel corn and dutchman's breeches use their far reaching feathery leaves to spread out and gather as much light as they can, then once they bloom and seed they die back until next year. Check out the photos below of how they look in spring - vs - now!  Reaching out from the ground, leafless stems spotted with tiny purple flowers can be spotted in damp wooded areas with a large concentration of beech trees. These "beechdrops" are parasitic and feed off the roots of the beech tree. Flowers can be found blooming August - October, but stems will remain all winter long.  Found mainly late summer to early fall in shady woods, the Virginia Knotweed can be found in large clusters. Sometimes known as Jumpseed, this perennial is known for its seeds which "jump" up to several feet when a ripe seedpod is disturbed. Its large oval leaves can be solid green or with a chevron shaped mark on the leaf; often individual plants will have both types of leaves. The goldenrod is in bloom and with it, for many, comes the sneezing and sniffling and all that comes with the all too familiar summer/fall allergies. Don't go chopping down that goldenrod just yet, goldenrod has gotten a bad rap due to the silent green flowers that grow nearby on the common & great ragweed plant!

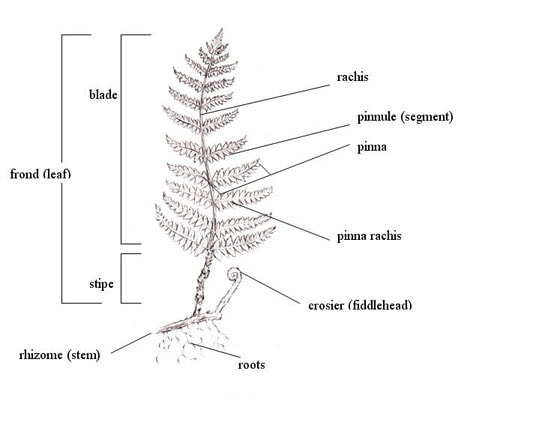

Goldenrod's pollen is too heavy to travel through the air causing allergies, in fact, only about .1% of people are actually allergic to it. Ragweed on the other hand is the late summer allergy villain growing in the same areas as goldenrod, blooming at the same time, but going unnoticed due to the flowers that blend in to the greenery around. Although it may be a bit late in the season for this, it doesn't hurt repeating.  Velvetleaf is one of those plants you don't notice until you look, then you see it everywhere - field edges, disturbed areas. Non-native (noxious in north west states) originating from China velvetleaf was brought to the Americas as a new source of fiber, especially for use as rope for ships. It was grown for about 100 years until it was abandoned for easier, more durable fibers. It is now found in all the lower 48. The name velvetleaf comes from the soft cottony texture of the leaves - can be used as tp in case of outdoor emergency. Seeds are edible. What are ferns? Where do they grow? How do they reproduce? What kind of fern is this? How long have they been around? We've all seen ferns, wether it's in the woods or in a local plant nursery, but what do you really know about these unique creatures from a long lost time? How long have ferns been around? Ferns first appeared roughly 360 million years ago, although the ferns we know today evolved around the time of the t-rex and triceratops during the cretaceous period 145 million years ago. What are they? They are a vascular plant meaning they have certain tissue that conducts water and nutrients throughout the plant. They have no flower or seeds and reproduce through spores. Where do they grow? While we're familiar with the ferns of moist shady forests, ferns can be found all over the world - high mountaintops, dry desert rock faces, in bodies of water, even in tropical trees. What determines where a type of fern will grow is dependent on the PH levels of the soil. In the highly acidic soil of bogs you can find lots of ferns! What are those tiny spots under the leaves? Those are the sporangia, tiny pods that hold the spores until mature. Once mature the ferns need either a big gust of wind or a rainstorm to allow the spores to be released from the sporangium. Not all ferns have the sporangia arranged in spots, sometimes they appear as solid lines under the leaf, sometimes as a solid border around the leaf, and in other cases you won't find any under the leaf - instead, usually early on, the plant will send up a fertile frond (often looks like a stick sticking up with a cluster on the end), the cluster is a modified pinnae where the sporangia can grow and release spores. Cinnamon Ferns get their names by the appearance of these fertile fronds. Parts of a fern. From the ground up, ferns form from a Rhizome in the ground, the Rhizome grows the Petiole or Stipe (stem of the fern before it branches or forms the blade), from the Petiole (Stipe) comes the Rachis (the part of the original stem that has the green). The Rachis is then broken down into a few different terms based on how the individual parts are attached. Pinnae and Pinnules are the primary and secondary divisions of the blade. The Veins are the thread-like vascular elements in the leaf tissue that define patterns. The Pinnae can have a wide range of edges - entire, crenate, serrate, dentate, and undulate. It sounds complicated, but check out the handy diagram from the University of Georgia below. How do I tell what kind of fern this is? Now that you know the different parts of the fern, by observing each part closely and noting the environment with which it's growing, you'll be able to grab a field guide and decipher just what type of fern you have. It's very important to note everything down to the hairs or scales on the stipe to make a 100% proper ID. However, in our parts there are some unique and easy to ID ferns. All of the ferns listed grow in moist shady forests. Cinnamon Fern - Tall up to 5ft, early fertile frond resembling a cinnamon stick. 1-pinnate, deeply pinnatifid. Christmas Fern - Evergreen, Pinnae can be described as looking like stockings (Christmas stocking). Sensitive Fern - What I call 'wobbly leaves'- sterile leaf deltoid-ovate, coarsely segmented, up to 2ft long. AKA Bead fern due to structure of sterile leaf. Royal Fern - Disguised as a small locust tree, ovate-lanceolate leaf. Fertile frond gives this fern its common name 'flowering fern'.  Lamb's Quarters is another very common weedy plant that can be found throughout most of the world and all of the Americas. In our area there are two different subspecies one native (Chenopodium album var. missouriense - Missouri lambs quarter) which is on the endangered list, the other introduced (Chenopodium album var. album - lambs quarter). This plant grows best in disturbed soils - barnyards, roadsides, cultivated fields. Each plant can produce up to 50,000 seeds and each seed has the capability of sitting dormant in soil for up to 40 years before growing! As with most non-native species, this plant is useful - it is a great source of vitamin A & C, leaves can be added to salads but it is best used either steamed or added to soups or curries (it is very abundant in India).  Common Mallow, aka - buttonweed, cheese plant, cheeseweed, is a non-native weedy plant found in waste areas, barnyards, etc. It is found all over the world from Asia to Africa to Europe to the Americas and with good reason too. This plant has many uses. All parts of the plant are edible. "The leaves can be added to a salad, the fruit can be a substitute for capers and the flowers can be tossed into a salad. When cooked, the leaves create a mucus very similar to okra and can be used as a thickener to soups and stews. The flavour of the leaves is mild. Dried leaves can be used for tea. Mallow roots release a thick mucus when boiled in water. The thick liquid that is created can be beaten to make a meringue-like substitute for egg whites. Common mallow leaves are rich in vitamins A and C as well as calcium, magnesium, potassium, iron and selenium."  Great Blue Lobelia is a native perennial blooming in late summer/ early fall in the eastern US. Its large showy flowers make it easy to spot and identify. Each flower is split into two 'lips' - the upper has two segments and the lower has three. This flower is the blue counterpart of the Cardinal Flower (bright red blooming about the same time). All parts of this plant are toxic, even though it once was supposed as a cure for syphilis (as reflected in its species name). I don't know about all of you, but September had me hopping from one project to the next - all very good things but I apologize for the limited updates. Don't fret though, this month there is a whole months' worth of interesting posts planned! Let's start by highlighting some of the awesome things I found while wandering through the woods last month. Caterpillars September brought the emergence of all sorts of different caterpillars below you can see the Tussock, Eastern Comma, and Monarch caterpillars! Willow Gall While out in the marsh I've come across a few of these, the leaves looked like a willow tree but it appeared to have a growth resembling a pinecone. At last I discovered it is a Willow Gall. Much like the galls on goldenrod (round bulges in the stem) this occurs when an insect (midge gall in this case) lays a single egg in a willow's terminal bud in spring. Chemicals injected by the female midge mixed with the chemicals exuded by the egg cause the willow to stop the elongating of the branch and instead causes the leaf tissue to broaden and Harden into the shape that resembles the scales on a pine cone. The larvae will then safely grow to adulthood and emerge from the gall leaving no harm done to the tree. Berries at peak At the end of summer, you'll see many berry bushes at full peak as they fruit and fall to create more plants for next year - or as is often the case - for birds and other animals to enjoy and spread the seeds. Below we have 'Dolls Eyes' aka White Baneberry, Solomon's seal, Solomon's Plume, and the Great Blue Cohosh in their fruiting glory.  Green Heron I was just excited to find a green heron out at the Killbuck Marsh Wildlife Area. The unique rushes and grasses showing off their seeded blooms. Below is the Soft Rush and Tawny Cotton Grass both found at the Bog. Harvestmen These are neither poisonous nor venomous as they spend their days eating small insects and plant matter. These daddy-long-legs are safe to handle, just be careful with them, they are fragile. Toad hole

While hiking out at Hampton Hills (Summit MetroParks) I came across a small hole in the trail - this isn't uncommon as chipmunks and even cicadas can leave holes in well packed trail dirt. As I walked closer a pair of eyes peered out at me, looking a little closer a nose appeared, then the shoulders, as I stood watching this little toad popped out and went on his way. Toads are capable of digging holes with their back legs, even in tough soil, using their urine as a softening agent for stubborn dirt. Wether this toad dug his own hole or made use of a pre-existing one I don't know, but I will keep a closer eye as I pass by these holes along the trail. As the leaves change and fall, the fog rises in the mornings, and the air turns crisp and sweet, we know fall is here.

Although the weather has yet to make up its mind as to if it's still summer or not, these cooler mornings have me feeling the fall. This is one of my favorite times to think about how the summer's growth has changed me for the better and to let that which does not serve me any longer fall away (see what I did there?). Today is a great day to consider how you've changed this year, how you want to grow in the future, and what you want/need to let go of to make that happen. Sipping a warm apple cider while doing so is advisable! :) |

AboutSince 2015 we have been exploring and sharing all the amazing things we’ve found in nature. AuthorEmily is an Ohio Certified Volunteer Naturalist who is most often found out in the woods. Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed